I think it's good when practitioners of conventional medicine listen with an open mind about alternative theories and practices.

In a similar vein, I think it's bad when practitioners of alternative medicine are closed-minded about conventional practices, and when conventional medicine is prematurely condemned and demonized.

A while ago, the strangeness of the general usage of the words "natural" and "artificial" struck me. Calling man-made things "artificial" seems to suggest that they are somehow less real than other things. Bees take material from plants and elsewhere, manipulate them in a complex process, and make honey -- honey that we call "natural" because humans didn't make it. When we manipulate substances, or build structures, it's "artificial." It really strikes me as a strange, arbitrary, artificial distinction.

Now it's true, some artificial things are bad for us -- but to stick to the example of bees, a lot of natural things are bad for us, too. Like bee venom.

But why I'm posting right now is because I was suddenly struck by the connection between this distinction in the human mind between natural and artificial, with artificial being bad or at least not as good as natural, and the traditional Judaeo-Christian view of humankind as being essentially wicked and depraved. What comes from a wicked, depraved being must be inferior to that which comes from God.

Of course, a practitioner or consumer of natural cures is not necessarily Jewish or Christian, nor does he or she consciously accept the traditional Judaeo-Christian doctrine of the depravity of mankind. But the mental distinction between natural and artificial seems to me to be a clear example of what Nietzsche described, at the beginning of the third book of Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft, as the shadow of the belief in God, which will endure long after people no longer believe in Him.

Monday, July 19, 2010

Friday, July 16, 2010

I Am a Fundamentalist Atheist

You may have heard or read the term "fundamentalist atheist," hurled by people who purport to be both religious and enlightened, to reconcile faith and reason, God and science. They see themselves as sensible moderates, as the only really sensible people in sight, actually, and decry "extremists" both of the fundamentalist religious and of the atheist type.

And sometimes they refer to us atheists -- or to an awful lot of us, anyway -- as fundamentalist atheists.

Well screw it, and screw them, I'm adopting the epithet and I'm going to wear it proudly. Many others before me have adopted an epithet and worn it proudly. "Gothic" as in gothic architecture was originally an insult. Gothic cathedrals still stand proudly, the insult is almost entirely forgotten. A similar sort of thing happened with the art movement known as les fauves (the wild beasts), and with punk rock. And now it has just happened again.

PS, 20. May 2015: I never was a fundamentalist atheist. I wrote this before I understood was is meant by the term. I did notice that it's a needlessly insulting term. If you want an atheist to stop listening to you, call him or her a fundamentalist atheist, that'll do the trick more than 9 times out of 10.

And sometimes they refer to us atheists -- or to an awful lot of us, anyway -- as fundamentalist atheists.

Well screw it, and screw them, I'm adopting the epithet and I'm going to wear it proudly. Many others before me have adopted an epithet and worn it proudly. "Gothic" as in gothic architecture was originally an insult. Gothic cathedrals still stand proudly, the insult is almost entirely forgotten. A similar sort of thing happened with the art movement known as les fauves (the wild beasts), and with punk rock. And now it has just happened again.

PS, 20. May 2015: I never was a fundamentalist atheist. I wrote this before I understood was is meant by the term. I did notice that it's a needlessly insulting term. If you want an atheist to stop listening to you, call him or her a fundamentalist atheist, that'll do the trick more than 9 times out of 10.

Friday, July 9, 2010

I Don't Care What Einstein Thought about God --

-- and I don't know whether I would ever have found it worth my while to mention that I don't care, were it not for the fact that so many people care so much about it -- specifically, theists and atheists arguing with each other, each claiming Einstein as belonging to their side. The debate centers mainly around two of Einstein's utterances: the famous remark that God doesn't play dice with the universe, and then, some time later, an expression of annoyance at the first remark having been misunderstood and a statement that he didn't believe in a personal God. Which of course leaves open the possibility that Einstein believed in an impersonal God, of the pantheistic or the watchmaker variety.

I am one of those atheists who's always arguing with believers, but, in the first place, it doesn't seem at all clear to me what Einstein believed on this subject, and in the second place, I don't see what it would matter if it were clear one way or another, because I see no evidence that he ever gave a lot of systematic, rigorous thought to the matter, the kind of thought he lavished so brilliantly upon physics. And as for Einstein's annoyance with his remark about God, the universe and dice having been misinterpreted, I think it was a very cryptic remark, as was his expression of annoyance. I don't see any evidence that Einstein ever had any clear thoughts on the question of the existence of God.

And furthermore, if I'm right, that one of the most brilliant scientists yet to inhabit this planet had nothing much to say about religion, I don't see anything particularly remarkable about that. Spinoza and Nietzsche both had a lot of intelligent things to say about religion; it was a central theme, if not the central theme, of both of their philosophical life's work. Both Einstein and Nietzsche admired Spinoza very much. But Einstein used language about God which was as cryptic as Spinoza's; but Einstein lived in a time which was much more tolerant of frank discussion of religion than Spinoza's time, and so he did not have Spinoza's excuse for -- relatively -- cryptic expression. Relatively: Spinoza still got into a lot of trouble expressing as much skepticism as he did. Nietzsche was very unmistakably clear on matters of religion, although theologians and Nazis, in my humble opinion, have still managed to completely misunderstand him.

Why should the fact that Einstein was so brilliant on the subject of physics have meant that he would be an authority on religion or any other subject? I don't know of anyone who's not stupid in some area of inquiry. Goethe, a Renaissance man after the Renaissance if ever there was one, a leading botanist and geologist and a fairly good draftsman as well as a poet and dramatist, still managed to be very wrong in some substantial ways about optics. So wrong that the young Arthur Schopenhauer, a protogee of Goethe's in Weimar, did not know how to resolve his differences of opinion with Goethe about optics except by leaving town. Which in turn is a very good example of how Schopenhauer, although very brilliant in very many ways, was anything but an expert in interpersonal relationships and conflict resolution. Nietzsche was brilliant in the area of religion, morality and ethics as they relate to nations and other large groups of people, and also when it came to pointing out errors in the thinking of other intellectuals, but he was very stupid on the subject of women.

Just as I am pretty smart in some areas -- for instance: when it comes to explaining how someone can be smart in one area and dumb in another -- and dumb in others, as are you, as is everyone else, if I don't miss my guess.

I am one of those atheists who's always arguing with believers, but, in the first place, it doesn't seem at all clear to me what Einstein believed on this subject, and in the second place, I don't see what it would matter if it were clear one way or another, because I see no evidence that he ever gave a lot of systematic, rigorous thought to the matter, the kind of thought he lavished so brilliantly upon physics. And as for Einstein's annoyance with his remark about God, the universe and dice having been misinterpreted, I think it was a very cryptic remark, as was his expression of annoyance. I don't see any evidence that Einstein ever had any clear thoughts on the question of the existence of God.

And furthermore, if I'm right, that one of the most brilliant scientists yet to inhabit this planet had nothing much to say about religion, I don't see anything particularly remarkable about that. Spinoza and Nietzsche both had a lot of intelligent things to say about religion; it was a central theme, if not the central theme, of both of their philosophical life's work. Both Einstein and Nietzsche admired Spinoza very much. But Einstein used language about God which was as cryptic as Spinoza's; but Einstein lived in a time which was much more tolerant of frank discussion of religion than Spinoza's time, and so he did not have Spinoza's excuse for -- relatively -- cryptic expression. Relatively: Spinoza still got into a lot of trouble expressing as much skepticism as he did. Nietzsche was very unmistakably clear on matters of religion, although theologians and Nazis, in my humble opinion, have still managed to completely misunderstand him.

Why should the fact that Einstein was so brilliant on the subject of physics have meant that he would be an authority on religion or any other subject? I don't know of anyone who's not stupid in some area of inquiry. Goethe, a Renaissance man after the Renaissance if ever there was one, a leading botanist and geologist and a fairly good draftsman as well as a poet and dramatist, still managed to be very wrong in some substantial ways about optics. So wrong that the young Arthur Schopenhauer, a protogee of Goethe's in Weimar, did not know how to resolve his differences of opinion with Goethe about optics except by leaving town. Which in turn is a very good example of how Schopenhauer, although very brilliant in very many ways, was anything but an expert in interpersonal relationships and conflict resolution. Nietzsche was brilliant in the area of religion, morality and ethics as they relate to nations and other large groups of people, and also when it came to pointing out errors in the thinking of other intellectuals, but he was very stupid on the subject of women.

Just as I am pretty smart in some areas -- for instance: when it comes to explaining how someone can be smart in one area and dumb in another -- and dumb in others, as are you, as is everyone else, if I don't miss my guess.

Wolff and Academic Vernaculars

It's been 18 years since the last time I dropped out of graduate school, but a lot of the things I read are similar to things that grad students would read. I've spent a significant portion of my life in university libraries and used-book stores; I did that before I was a university student, and between the periods when I was enrolled in one university or another, and when I was enrolled I spent a lot of time in such places researching a lot of things which did not have to do with the courses I was taking at the time. At the moment I'm waiting for a volume of letters between Leibniz and Wolff to arrive via UPS, a title whose audience, I'm guessing, consists mostly of professional academics; the tracking information indicates it should arrive today.

to arrive via UPS, a title whose audience, I'm guessing, consists mostly of professional academics; the tracking information indicates it should arrive today.

Latin letters: the German title of the book is Briefwechsel (in lateinischer Sprache), Correspondence (in the Latin Language). I suspect that the subtitle in parentheses may be meant to indicate that Leibniz and Wolff also corresponded in other languages, but the present volume presents only the Latin letters. I ordered the book because of my interest in Leibniz, with Wolff's name ringing only the faintest of bells; after I ordered it I checked the Wikipedia article on Wolff -- Christian von Wolff -- and it says that he was the most eminent German philosopher between Leibniz and Kant, and that it was he who introduced the use of German as a language of scholarly instruction and research. (So, it was him! He's the one!) Wolff lived from 1679 to 1754. There was still a lot of German scholarly writing in Latin after him -- see for instance this collection of articles by August Boeckh, written between the 1810's and the 1840's, or the two pieces in Latin written by Nietzsche in the 1860's included in this collection;

written between the 1810's and the 1840's, or the two pieces in Latin written by Nietzsche in the 1860's included in this collection; but both the Boeckh and the Nietzsche are articles having to do with Classical literature, where it's only to be expected that the use of Latin as a vernacular would persist longer than in other fields.

but both the Boeckh and the Nietzsche are articles having to do with Classical literature, where it's only to be expected that the use of Latin as a vernacular would persist longer than in other fields.

Also, it seems to me, although as yet I have no way at all of proving it, that academic papers and lectures must have been written and read in German at least now and again before Wolff.

Still, I don't see any particular reason to doubt that Wolff at least greatly popularized the use of German and the partial abandonment of Latin in German universities. It seems to me that there must have been some controversy over this; I'm picturing polemics published for and against the use of German in academia. I'm picturing most or all of them written in Latin, on both sides of the question. Reader, you may consider me to be already actively looking for those polemics exchanged between 18th-century academics. I'm on the side that lost, and I'm annoyed with those earlier scholars who lost the cause. I'm picturing pro-Latin polemics full of faulty reasoning, ad hominem attacks, reactionary politics, contempt for the lower classes, and a pronounced lack of charm in general: with some exceptions, a good cause badly argued, and on the other side, very bright and good men, and perhaps even some ladies, holders of salons perhaps, arguing brilliantly and movingly on the wrong side. Cheered on by horses' asses like Rousseau and Paine.

Now the cause of the revival of Latin is a positively Quixotic one, argued by a few weirdos such as myself. I don't think it's impossible that Latin will one day once again be a widespread common language of academia, re-establishing a international, non-nationalistic Latin culture, and not just in Classical studies and related disciplines, either, or even in wider circles than academia; but that's mainly because I think it's logically unsound to make predictions about human behavior using the term "impossible." Even I admit that it's extremely unlikely.

Latin letters: the German title of the book is Briefwechsel (in lateinischer Sprache), Correspondence (in the Latin Language). I suspect that the subtitle in parentheses may be meant to indicate that Leibniz and Wolff also corresponded in other languages, but the present volume presents only the Latin letters. I ordered the book because of my interest in Leibniz, with Wolff's name ringing only the faintest of bells; after I ordered it I checked the Wikipedia article on Wolff -- Christian von Wolff -- and it says that he was the most eminent German philosopher between Leibniz and Kant, and that it was he who introduced the use of German as a language of scholarly instruction and research. (So, it was him! He's the one!) Wolff lived from 1679 to 1754. There was still a lot of German scholarly writing in Latin after him -- see for instance this collection of articles by August Boeckh,

Also, it seems to me, although as yet I have no way at all of proving it, that academic papers and lectures must have been written and read in German at least now and again before Wolff.

Still, I don't see any particular reason to doubt that Wolff at least greatly popularized the use of German and the partial abandonment of Latin in German universities. It seems to me that there must have been some controversy over this; I'm picturing polemics published for and against the use of German in academia. I'm picturing most or all of them written in Latin, on both sides of the question. Reader, you may consider me to be already actively looking for those polemics exchanged between 18th-century academics. I'm on the side that lost, and I'm annoyed with those earlier scholars who lost the cause. I'm picturing pro-Latin polemics full of faulty reasoning, ad hominem attacks, reactionary politics, contempt for the lower classes, and a pronounced lack of charm in general: with some exceptions, a good cause badly argued, and on the other side, very bright and good men, and perhaps even some ladies, holders of salons perhaps, arguing brilliantly and movingly on the wrong side. Cheered on by horses' asses like Rousseau and Paine.

Now the cause of the revival of Latin is a positively Quixotic one, argued by a few weirdos such as myself. I don't think it's impossible that Latin will one day once again be a widespread common language of academia, re-establishing a international, non-nationalistic Latin culture, and not just in Classical studies and related disciplines, either, or even in wider circles than academia; but that's mainly because I think it's logically unsound to make predictions about human behavior using the term "impossible." Even I admit that it's extremely unlikely.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Textual Transmission

The transmission of a text is the process by which it goes from the original writing of the author to the reader. In the case of a letter written today, usually the reader has before him the exact version written by the author. On an Internet forum or message board, a moderator may change something in the original text before it is presented to the reader, putting one more step between author and reader.

In the case of older texts, written in ancient or medieval times, things may be more complicated, many more steps may be involved. In other words: the transmission may be much more complicated.

Scholars have found some of the original copies of personal letters and shopping lists and written instructions from an employer to an employee, things like that, from the Middle Ages and some even from before. For example, this letter, one of thousands of pieces of ancient papyrus unearthed at the site of the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, has been dated to the 2nd century AD:

It has been translated as follows:

Thais to her own Tigrius, greeting.

I wrote to Apolinarius to come to Petne for the measuring. Apolinarius will tell you how the situation stands concerning the deposits and public dues. He will let you know the name of the person involved.

If you come, take out six measures of vegetable seed and seal them in the sacks, so that they may be ready. And if you can, please go up and find out about the donkey.

Sarapodora and Sabinus salute you. Do not sell the young pigs without consulting me. Good bye.

Not an earthshaking communication, perhaps, but if one examines a lot of such documents, together they may be very helpful in forming a mental picture of past places and times.

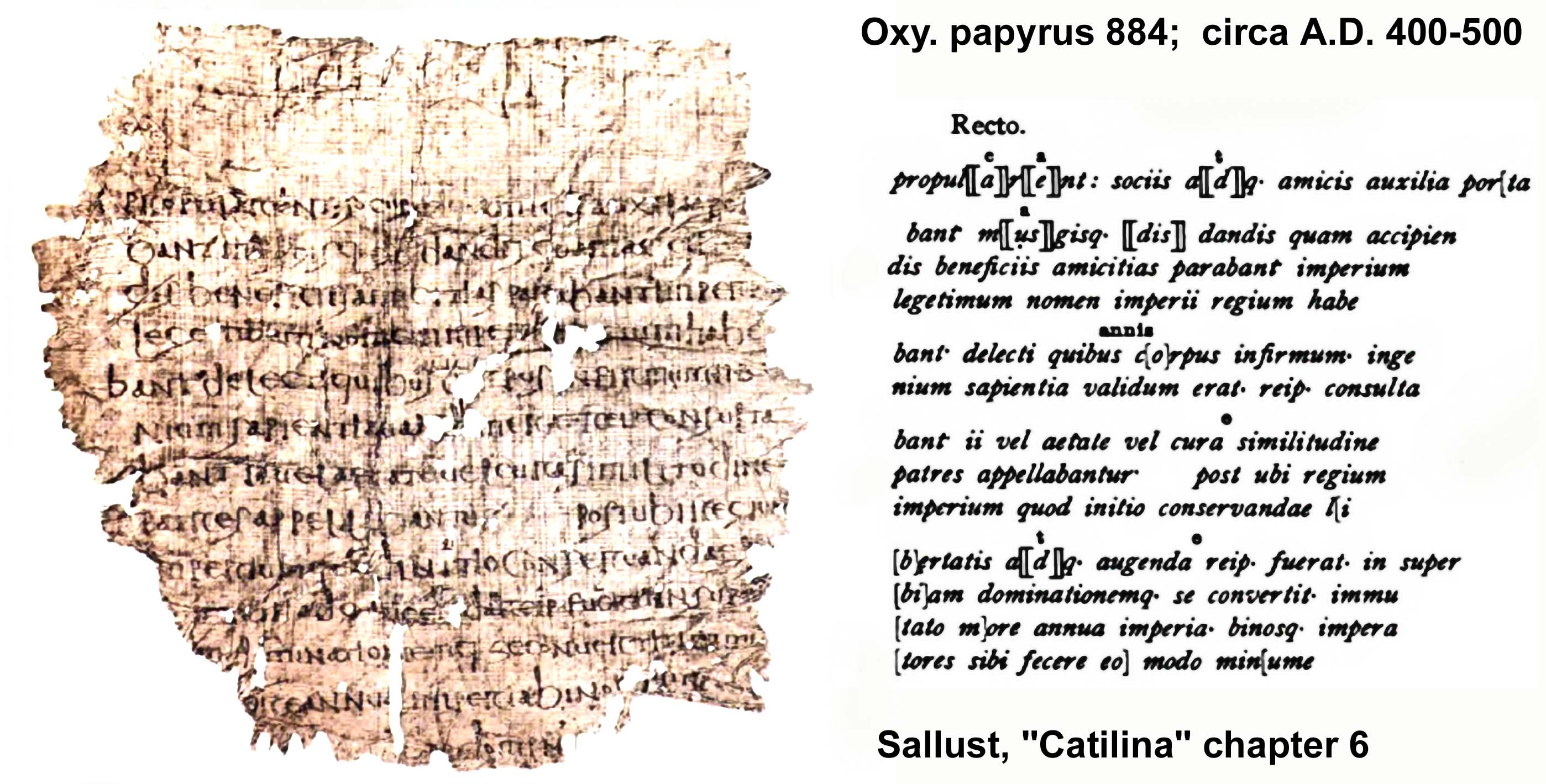

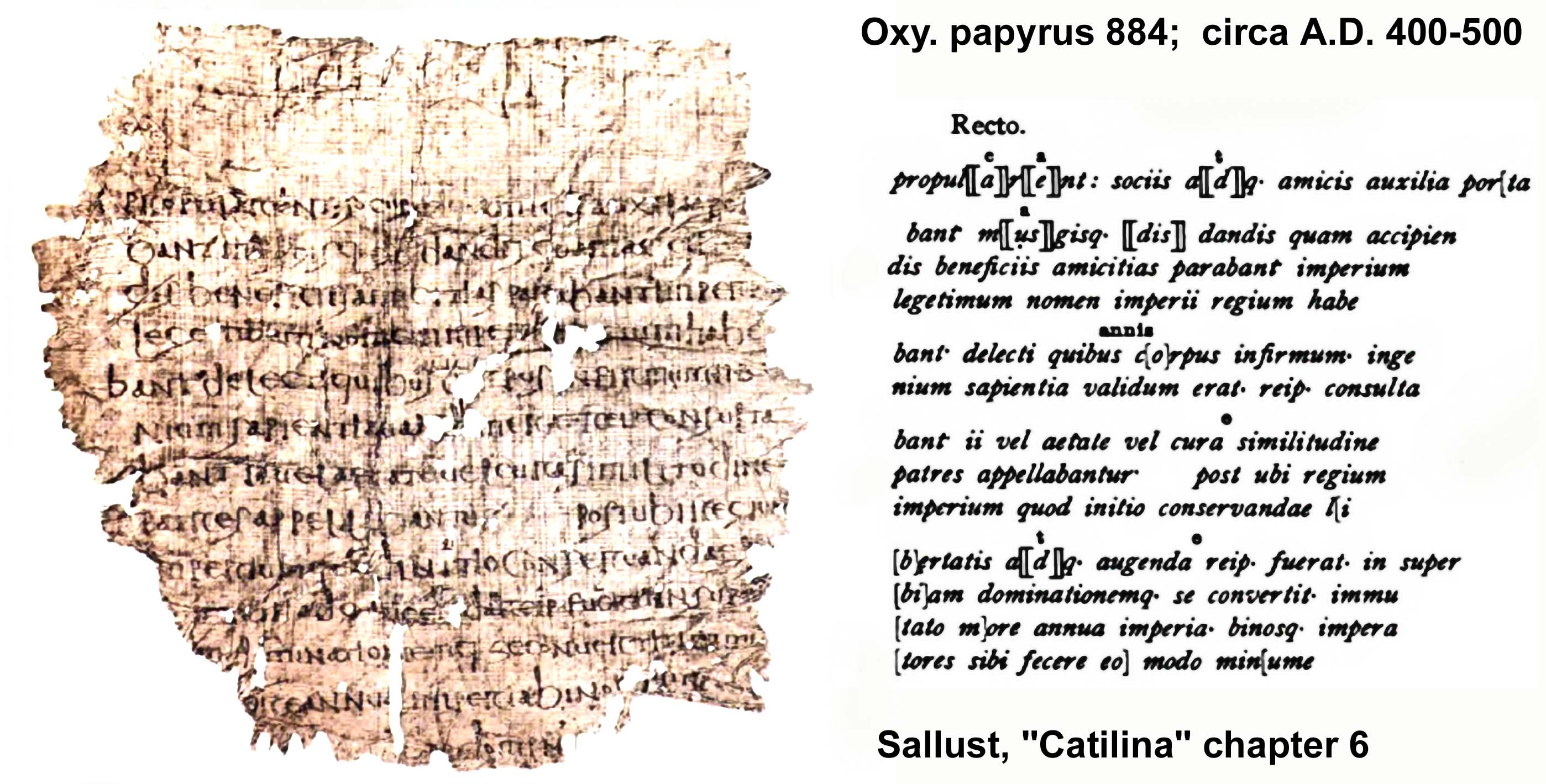

Then there are the texts referred to as "literary," intended for a larger audience: besides the genres we may think of as "literature" in a narrower sense, fiction and poetry and drama, these include works of history and philosophy and science. There's just one copy, from before the age of mechanical and electronic reproduction, of Thaius' letter to Tigrius, presumably either written in Thaius' own hand or dictated to a servant. There may be many copies of a given ancient literary text, but it's rare to find one made within even several centuries of its original composition. For example, as I recently found out, in the case of Sallust' histories of the Cataline conspiracy and the Jugurthine War, written in the 1st century BC, there appear to be over 500 manuscripts in publicly-accessible collections today. But apart from 4 fragments preserved in scraps of papyrus from the 4th and 5th centuries, none of these manuscripts is older than the 9th century. Here's the left edge of one of those papyri:

The fact that several of the manuscripts of Sallust's works are as old as the 9th century is very good. The fact that there are also some older ones known, even if they are just scraps, is exceptional. It's good from a point of view of the manuscripts as objects from the 9th century of historical interest in their own right, and it's also good on the general assumption that the older a manuscript is, the greater the chances are that it preserves the original text, that which Sallust actually wrote, with some sort of accuracy. That's a very general assumption. We don't generally know, for any given manuscripts of an ancient text, how many copies may lie between it and the original. A 4th-century papyrus may be a very sloppy copy of a very sloppy copy of a very sloppy copy... repeat many more times, of the original. On the other hand, a 15th century manuscript may be a very accurate copy of a very much older manuscript which was copied from Sallust's own personal copy. Manuscripts are judged on other criteria than age. But generally speaking, for those interested in accurately reconstructing the original text of an ancient author, when it comes to manuscripts, old is good and very old is very good.

And with very few exceptions, until the last couple of centuries, 9th century was about as old as any surviving manuscripts of pre-Christian Classical authors were. This is one of the main reasons why so many scholars point to the reign of Charlemagne as the end of the Dark Ages: because he instituted an educational program, including the study of those ancient pagans, and many of those 9th-century copies were made because of him. So why don't we have many of the copies from which the 9th-century copies were made? Because, before the Italian Renaissance in the 14th century, it rarely seems to have occurred to anyone in Western Europe that a manuscript -- or a building or anything else -- might be worth preserving simply because it was old. New copies were made, and the old, worn-out ones were thrown out. Some of those pre-9th-century exceptions include 8 4th and 5th century manuscripts of Vergil, and 4 5th century manuscripts of Livy -- at least 4. I know of 4, in addition to some of the papyri described below.

Many more older manuscripts have been found by archaeologists from the 19th century onward, written on papyrus and buried in the desert south and east of the Mediterranean, where, it turns out, papyrus can last for a very, very long time without decomposing. By far the most famous of these finds has been the Dead Sea Scrolls, but that discovery was just one of many. Most of the finds have just been scraps, like the papyrus of Sallust illustrated above, but still, because of their age, they're very exciting to students of ancient literature.

Here's a fragment of the Gospel of John, believed to have been copied out in the first half of the 2nd century, very close to the time that this text was originally written:

Speaking strictly as a layman, let that be perfectly clear, the general impression I get from the comparisons of these discoveries of old papyri with medieval manuscripts and with modern editions of ancient texts is that the medieval scribes tended to be very scrupulous and accurate and that the modern editors tend to be very good at their jobs. I know I could never do what they have done, and I'm very grateful for their efforts.

In the case of older texts, written in ancient or medieval times, things may be more complicated, many more steps may be involved. In other words: the transmission may be much more complicated.

Scholars have found some of the original copies of personal letters and shopping lists and written instructions from an employer to an employee, things like that, from the Middle Ages and some even from before. For example, this letter, one of thousands of pieces of ancient papyrus unearthed at the site of the ancient city of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, has been dated to the 2nd century AD:

It has been translated as follows:

Thais to her own Tigrius, greeting.

I wrote to Apolinarius to come to Petne for the measuring. Apolinarius will tell you how the situation stands concerning the deposits and public dues. He will let you know the name of the person involved.

If you come, take out six measures of vegetable seed and seal them in the sacks, so that they may be ready. And if you can, please go up and find out about the donkey.

Sarapodora and Sabinus salute you. Do not sell the young pigs without consulting me. Good bye.

Not an earthshaking communication, perhaps, but if one examines a lot of such documents, together they may be very helpful in forming a mental picture of past places and times.

Then there are the texts referred to as "literary," intended for a larger audience: besides the genres we may think of as "literature" in a narrower sense, fiction and poetry and drama, these include works of history and philosophy and science. There's just one copy, from before the age of mechanical and electronic reproduction, of Thaius' letter to Tigrius, presumably either written in Thaius' own hand or dictated to a servant. There may be many copies of a given ancient literary text, but it's rare to find one made within even several centuries of its original composition. For example, as I recently found out, in the case of Sallust' histories of the Cataline conspiracy and the Jugurthine War, written in the 1st century BC, there appear to be over 500 manuscripts in publicly-accessible collections today. But apart from 4 fragments preserved in scraps of papyrus from the 4th and 5th centuries, none of these manuscripts is older than the 9th century. Here's the left edge of one of those papyri:

The fact that several of the manuscripts of Sallust's works are as old as the 9th century is very good. The fact that there are also some older ones known, even if they are just scraps, is exceptional. It's good from a point of view of the manuscripts as objects from the 9th century of historical interest in their own right, and it's also good on the general assumption that the older a manuscript is, the greater the chances are that it preserves the original text, that which Sallust actually wrote, with some sort of accuracy. That's a very general assumption. We don't generally know, for any given manuscripts of an ancient text, how many copies may lie between it and the original. A 4th-century papyrus may be a very sloppy copy of a very sloppy copy of a very sloppy copy... repeat many more times, of the original. On the other hand, a 15th century manuscript may be a very accurate copy of a very much older manuscript which was copied from Sallust's own personal copy. Manuscripts are judged on other criteria than age. But generally speaking, for those interested in accurately reconstructing the original text of an ancient author, when it comes to manuscripts, old is good and very old is very good.

And with very few exceptions, until the last couple of centuries, 9th century was about as old as any surviving manuscripts of pre-Christian Classical authors were. This is one of the main reasons why so many scholars point to the reign of Charlemagne as the end of the Dark Ages: because he instituted an educational program, including the study of those ancient pagans, and many of those 9th-century copies were made because of him. So why don't we have many of the copies from which the 9th-century copies were made? Because, before the Italian Renaissance in the 14th century, it rarely seems to have occurred to anyone in Western Europe that a manuscript -- or a building or anything else -- might be worth preserving simply because it was old. New copies were made, and the old, worn-out ones were thrown out. Some of those pre-9th-century exceptions include 8 4th and 5th century manuscripts of Vergil, and 4 5th century manuscripts of Livy -- at least 4. I know of 4, in addition to some of the papyri described below.

Many more older manuscripts have been found by archaeologists from the 19th century onward, written on papyrus and buried in the desert south and east of the Mediterranean, where, it turns out, papyrus can last for a very, very long time without decomposing. By far the most famous of these finds has been the Dead Sea Scrolls, but that discovery was just one of many. Most of the finds have just been scraps, like the papyrus of Sallust illustrated above, but still, because of their age, they're very exciting to students of ancient literature.

Here's a fragment of the Gospel of John, believed to have been copied out in the first half of the 2nd century, very close to the time that this text was originally written:

Speaking strictly as a layman, let that be perfectly clear, the general impression I get from the comparisons of these discoveries of old papyri with medieval manuscripts and with modern editions of ancient texts is that the medieval scribes tended to be very scrupulous and accurate and that the modern editors tend to be very good at their jobs. I know I could never do what they have done, and I'm very grateful for their efforts.

Thursday, July 1, 2010

So There I Was --

-- just now, in the grocery store, and I don't know, maybe I looked especially approachable because Santana's version of "Oye como va" had just played on the PA, and I may not have been completely successful in my attempt to prevent my appreciation of the song from expressing itself in a goofy physical manner, because, as someone once said -- I think maybe it was someone who used to play for James Brown, maybe it was Maceo hisself, in any case it was someone who was making a lot of sense -- funk is music which causes yer head and neck and shoulders to move in ways in which they ordinarily would not, and Santana's version of that tune may not usually be categorized as funk, I wouldn't know, ask someone who likes to categorize things, but it's funky and then some. And maybe I was especially susceptible to that funk because mere moments before, in my car in the parking lot, I was listening to the end of "Burning Down the House" by Talking Heads, where Chris Franz gets especially expressive on the drums. Again, I don't know if people usually call that funk, but it is. So I was already dancing in my car seat before I got to the store.

(And in general, I think that when you reach the end of your life, whether or not you enjoyed yourself, for example by dancing in the grocery store or singing along to music in car and dancing in the driver's seat, will have mattered more than if you looked silly, now and then, for example by singing in your car or dancing in the store. I get embarassed, just like other people. Only -- less, I think.)

Or maybe I just look like a goofy approachable mark no matter what music is playing. (Maybe they can all see that I have Asperger's or something weird, ayeee!) Or maybe it had nothing at all to do with how I looked or what I was doing. (Maybe most people are actually jealous of me because I'm so cool, and they think, Gee, look at the big stocky guy enjoying himself so much! I wish I could overcome my inhibitions and enjoy life and really live it like that big stocky guy is doing. Look at him dancing in his driver's seat! He looks like he could lift a car wheel off the ground without a jack, he's so big and tough I swear! He's so cool!) Maybe they just needed to fill a quota, bad. For whatever reason, as I passed the stand where, then as so often, representatives of a local metro newspaper were attempting to perpetrate something, one of the people behind the stand accosted me, saying I could win one hundred dollars. I felt it would be impolite to just walk past, ignoring the two of them, so I attempted to express disinterest politely. But an entry slip was thrust at me. All I had to do was fill it out! A hundred bucks! C'mon! Among other blanks on the slip, I saw one for my phone number and another for my e-mail, and I said, Yeah, but then my info would be on a list, and was about to move on, but the other person behind the stand, a burly guy with lots of tats, went. Off.

The bank had already sold all of my info to everyone! he exclaimed. Everybody who wanted my info already had it!

I moved on. A couple of seconds later it occurred to me to call back over my shoulder: "You don't!"

I don't know whether he heard me.

(And in general, I think that when you reach the end of your life, whether or not you enjoyed yourself, for example by dancing in the grocery store or singing along to music in car and dancing in the driver's seat, will have mattered more than if you looked silly, now and then, for example by singing in your car or dancing in the store. I get embarassed, just like other people. Only -- less, I think.)

Or maybe I just look like a goofy approachable mark no matter what music is playing. (Maybe they can all see that I have Asperger's or something weird, ayeee!) Or maybe it had nothing at all to do with how I looked or what I was doing. (Maybe most people are actually jealous of me because I'm so cool, and they think, Gee, look at the big stocky guy enjoying himself so much! I wish I could overcome my inhibitions and enjoy life and really live it like that big stocky guy is doing. Look at him dancing in his driver's seat! He looks like he could lift a car wheel off the ground without a jack, he's so big and tough I swear! He's so cool!) Maybe they just needed to fill a quota, bad. For whatever reason, as I passed the stand where, then as so often, representatives of a local metro newspaper were attempting to perpetrate something, one of the people behind the stand accosted me, saying I could win one hundred dollars. I felt it would be impolite to just walk past, ignoring the two of them, so I attempted to express disinterest politely. But an entry slip was thrust at me. All I had to do was fill it out! A hundred bucks! C'mon! Among other blanks on the slip, I saw one for my phone number and another for my e-mail, and I said, Yeah, but then my info would be on a list, and was about to move on, but the other person behind the stand, a burly guy with lots of tats, went. Off.

The bank had already sold all of my info to everyone! he exclaimed. Everybody who wanted my info already had it!

I moved on. A couple of seconds later it occurred to me to call back over my shoulder: "You don't!"

I don't know whether he heard me.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)